roman orthography & syllabics

This was originally published on hundreds.ca/notebook on July 2, 2017. Many developments in Cree Syllabic typoography have occurred since this time. Typotheque has some good articles on this topic. and so Kevin Brousseau’s blog.

Wild Berries; Pikaci-Minisa; ᐸᐠᐘ ᒋ ᒥᓂᓴ; Pakwa che Menisu

Context

In working on book design projects with Cree text, I found some information hard to find just by googling and sometimes I felt confused. I'm going to share my notes for anyone who, like I did, needs a bit of a primer to get oriented. This is partly a place to send my typography students as a step to further resources when we cover non-roman orthography and emerging typographic practices in class. It's also a place for me to go through all my notes and put them in one place, which helps me understand better myself.

There are lots of great resources for anyone who would like to get a better understanding of the Cree language, which I'll put at the top of the post. I am not an authority on Cree, and only hope to provide some context for designers from outside the community, as a typesetter, who would like to prepare to work with Cree text. Arden Ogg & Dorothy Thunder have both taken time to answer questions from me over the past few years, and I'm really grateful to them for their time.

The specific text examples I am using here are mostly from books by Julie Flett set in several Western Cree dialects, because they are projects I've worked on, and where I learned a lot of this information. This post will be looking at Cree set in roman orthography and in Western syllabics.

Title page of Pakwa che Menisu, alternate edition of Wild Berries, by Julie Flett

Type notes:

Pakwa che Menisu is set in a serifed roman face called Californian

ᐸᐠᐘ ᒋ ᒥᓂᓴ set in a syllabic font called Maagonigan

Julie Flett set in Poetica, a font modelled on chancery script (an italic)

Resources

Good Cree language resources include Cree Literacy Network, Indigenous Languages of Manitoba Inc., and Cree Dictionary. Chelsea Vowel has a lot of good learning resources collected here as well.

Standardization and variation

There are over sixty Indigenous languages spoken north of the Canada/US border. Cree is one of the most commonly spoken, with over 83,000 speakers. There is only one Plains Cree immersion elementary school at the moment — this article explains the values and challenges of the Cree immersion program at Onion Lake. (Assembly of First Nations has recently put together a collection of resources that addresses broader goals and educational needs, offering a holistic perspective on a First Nations educational model that gives additional context, available in iTunes).

Solomon Ratt: Elements of Cree Culture in y-dialect from Cree Literacy Network; Audio with pronunciation read by Solomon is available at link

Dialects

Cree dialects are often named in three ways. For example, the y-dialect spoken in Alberta and southern Saskatchewan, is also known as nêhiyawêwin or Plains Cree. Variations can occur within a dialect. For example Wild Berries is in n-dialect from the Cross Lake, Norway House area as well as in n-dialect from the Cumberland House area (n-dialect is also known as Swampy Cree). Both are n-dialect, but they have differences according to community, including different community preferences for roman orthography or syllabics.

Pronunciation, wording, and spelling can vary speaker to speaker as well as region to region. In Julie Flett's book about colour, Black Bear, Red Fox, Arden Ogg writes in the preface, of the different colour names listed in the book:

If you talk to other speakers of Plains Cree, they may use different terms, or combinations of terms from the ones we use here, that are still correct. The colour words used in this book were selected by one particular speaker on one particular day: on a different day, even that same speaker may have chosen differently.

In written English, there are regional variations in terms and spelling, too, like English and American spellings (colour vs. color). However, text has to be standardized within the same text or everyone gets quite stressed out. A copy editor generally wouldn't allow both "colour" and "color" to appear in the same text. Standardization is so prioritized that a copy editor will sometimes allow a style that is not their preference, as long as it's the same throughout the text. I don't know if this is purely developed out of print culture, the codex system, or if it's a reflection of larger cultural beliefs (a colonial perspective of a "right way" and a "wrong way"?) or something else. I didn't really notice it as a bias in publishing practices until the first time I got copyediting notes back on a Cree text that were not approved by the translator. (English wasn't always so rigidly standardized...I feel like there are some things to be explored here.)

Along with variations in wording, multiple spellings of the same word may appear in the same book, or even the same text (say a word is spelled differently in a headline than in the body), a copy editor may be asked to accommodate this variation in the spellings. I've seen this cause stress in more than one English-oriented copy editor. Based on my limited experience, it's ok and appropriate to allow Cree spelling not to be standardized throughout a book, especially if it is the wish of the writers or translators being consulted. It might be a good thing to have editorial discuss this at the beginning of the project.

One last thing about colour. Arden Ogg also writes:

In Cree, speakers may use the word osâwi- for yellow, orange or brown. They may use the word sîpihko- for blue, green, or grey. They may also create new colour words — as in the English language — by combining the colour words from the chart with each other, or by modifying them with wâp- (meaning ‘bright’ or ‘light’), and kaskitê- (meaning ‘dark’ or ‘black’).

I just want to pause for a second to say how much this reminded my of Muji designer Kenya Hara's note on traditional 8th century Japanese colour naming, "The basic adjectives at that time were just four...akai (red); kuroi (black); shiroi (white); and aoi (blue)...These adjectives may strike us as too few [but] There was no need to classify colors as strictly as we do today...blue and green...could be lumped together emotionally under the broader category of aoi (blue)." He goes on to say that a person referring to a more specific colour would use an item like "blood orange" or "young grass" to name it. Colour is a partially subjective experience, like sound, and both these systems allow for a more personal and specific way of describing colour that allow for expressive communication in a way that I really enjoy thinking about.

Grammar

I have the impression that wording in Cree phrases is often not perfectly modular — and you have to be careful not to pull words out of context (as in any language). Arden Ogg writes, "In English, we learn to name our colours just as we name shapes or animals. Cree works differently. In Cree, verbs must change their shape to match the associated nouns (similar to French) which are classified as animate or inanimate. Because colour words in Cree are verbs (action words), we need to learn both animate and inanimate forms for every colour, and we need to know whether each noun is animate or inanimate. If a noun is plural, the colour verb must be plural too."

So red as a prefix in Plains Cree in this example is mihko, but to describe a single red fox takes on the singular animate form and becomes mihkosiw mahkêsîs. I couldn't pull mihkosiw from this phrase use it to mean red in any context. Also, as noted above, from my understanding "red" could be described differently.

From Black Bear, Red Fox by Julie Flett. Red Fox in the y-dialect spoken in Alberta and southern Saskatchewan, also known as nêhiyawêwin or Plains Cree

Syllabics and standard roman orthography

Standard roman orthography (or SRO — sometimes called Roman Syllabic Orthography or RSO) refers to words that are written in the roman or latin alphabet, which is what English speakers and many other European languages use (there are variations on pronunciation, like ch for the letter "c" for example, but the glyphs are the same) as well as 4 accented long vowels (3 in Woods Cree, where ê and î are merged. Woods Cree also has the phoneme th /ð/ (the th). The long vowels are: â as in father, ê as in pay, î as in keep, ô as in boat

Sometimes Cree, depending upon language or community preference, is written in syllabics instead of roman orthography. Western and Eastern syllabics have some differences.

I am going to use the word "grandmother" to illustrate variations in both SRO and syllabics for this word, taken from two editions of Wild Berries by Julie Flett. In one edition, the text is set in English and n-dialect, also known as Swampy Cree, from the Cumberland House area. The second edition was set in Swampy Cree from the Cross Lake, Norway House area. This second edition was set in SRO and syllabics (with no English).

Below is ôkoma (grandmother) in Swampy Cree from the Cumberland House area, described as being pronounced oo-co-muh in this edition of the book. It is set in SRO. The accent over the o can be either a cirumflex ˆ or a macron, as in the text below

Wild Berries by Julie Flett

Below is that text set in Swampy Cree from the Cross Lake, Norway House area (in this version the SRO okoma has no accent). The same text is repeated below the SRO (black) in syllabics (red).

Pakwa che Menisu by Julie Flett

Two screen shots of roman type in a converter to Woodland and Plains Cree syllabics

For Pakwa che Menisu, I received a text document from the translator set in roman orthography, and another set in syllabics. The first challenge for me was that I could not make the text document with the syllabics work with my layout program (InDesign). The converter was able to take the SRO text the translator provided, which I typed in, and convert it into syllabics, which I could then copy and paste into InDesign. So it bridged a technical difficulty.

The converter offered only only Maskwacis, Plains, and Woodland Cree, not Swampy Cree. This confused me, but I found that in general all converters of these Western Cree dialects translated the text into syllabics which matched the Swampy Cree text I'd been given. Even the Eastern Cree converter was very consistent. This is just one example, since I only did this conversion process once. This note from Kevin Brousseau’s blog on specific glyphs is one example of variations that different dialects might have. Plain syllabics and pointed syllabics (syllabics with additional dots to help beginners) are another type of variation.

To render the syllabics in InDesign, a font that supported the syllabics was installed in FontBook (in this case Maagonigan). Once the syllabics were pasted into InDesign, I could check the syllabic sequence against the text document (which I could see as a preview) to see that it was matching.

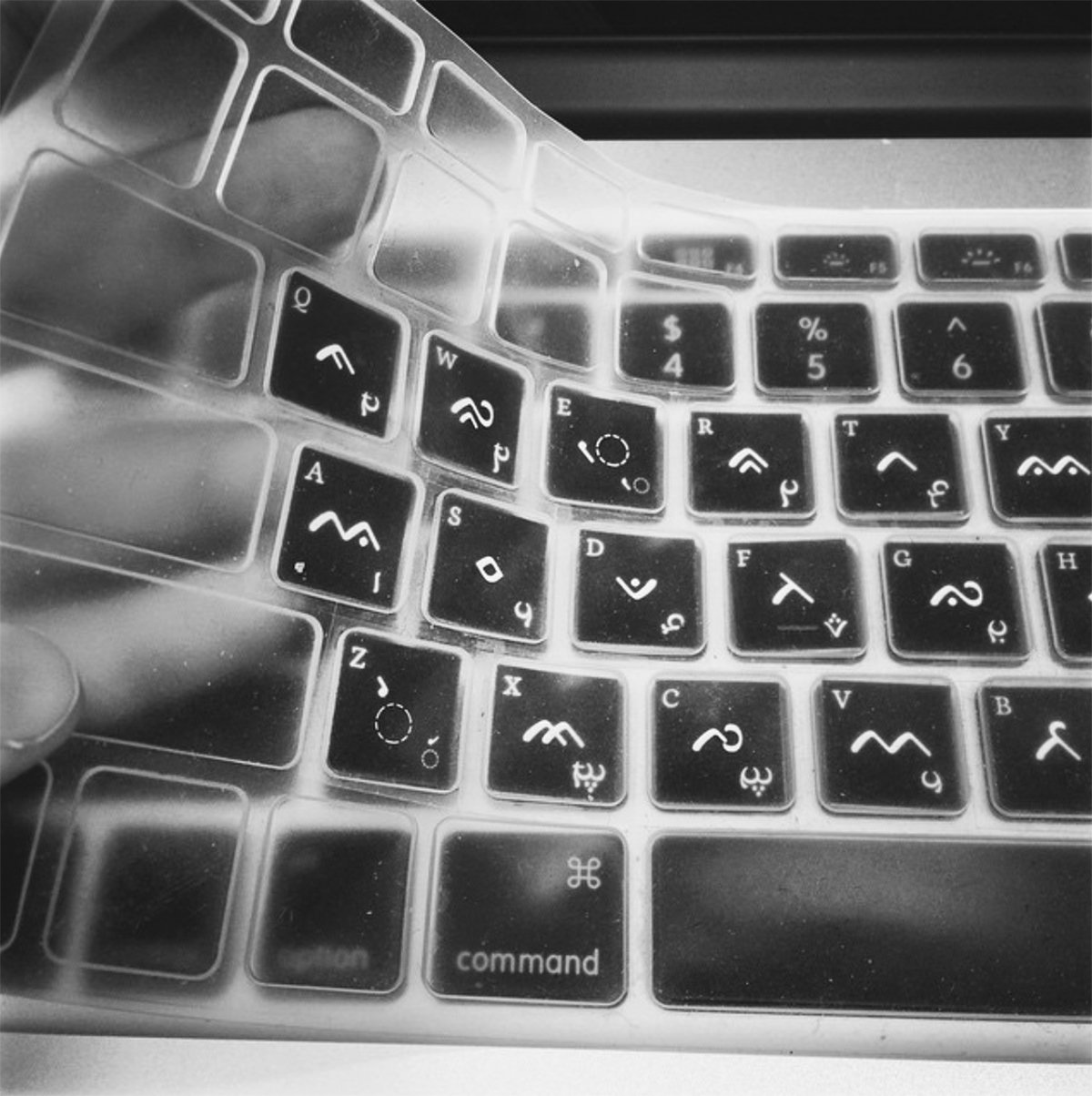

Keyboard for a PC (l) & Western Cree & Eastern Cree phone keyboards from Christopher Horsethief (r)

The phone keyboard screenshots aren't showing the full range of syllabics for either Western or Eastern Cree, so there are glyphs showing on each keyboard that are common to both syllabary — they're not completely separate alphabets.

Cree keyboards

I haven't installed a Cree keyboard, but I know it can be done for PCs and for iPhones. I would assume making it easier to switch between keyboards on phones and PCs would help encourage younger speakers in communities which use syllabics:

In supporting any community using an alphabet which isn't roman, the qwerty keyboard default seems like it would be an annoyance. Annoyances can really influence behaviour. So making non-roman keyboards more intuitive or accessible with a minimum number of movements/clicks/actions seems like it could be potentially be very helpful in fostering literacy. I feel like I should mention here that some literacy advocates prefer roman orthography because it may come with less challenges, possibly removing extra barriers to to literacy. I don't feel that it's my place to speak on that, but as a typography and communications teacher, it is a conversation that I am interested in hearing more about. It's possible that digital technology opens up new possibilities for accommodating multi-alphabet systems more easily (which I need to write out in a separate post). In the meantime, I acknowledge the points of view of people working in literacy who prefer roman orthography and to those communities and teachers who prefer syllabics. As a designer, I think I don't need to put my oar in this conversation, but just have ability to accommodate both approaches in my layout.

adapting a keyboard for a non-roman alphabet, via alphabettes

I think this homemade Buginese keyboard cover that I saw on Alphabettes is pretty brilliant (?). I'm sure there are lots of qwerty-conversion keyboard tricks out there that I just haven't seen yet. This would be a good discussion to start having in design programs. (Buginese is from South Sulawesi, Indonesia — like Cree which is set in syllabics it is an alphabet that is non-roman).

Fonts which support Western syllabics

Syllabic fonts

There aren't a wide variety of syllabic fonts available yet. Availability of fonts for non-roman typographic systems is an important part of emerging typographic practices. I did find more in looking this year, so that's good news. I'm still becoming educated about syllabics, and hope to eventually have gathered enough information about legibility and readability to introduce it in my classes.

Tiro Typeworks offers Euphemia by donation. They will soon release Wawatay. Both support Cree and Inuktitut. Languagegeek offers several syllabic fonts with a specific list of languages and dialects supported as well.

If you happen to come across this and have anything to add or correct, please let me know!