Kyiv & Paris

This was originally published on hundreds.ca/notebook on June 4, 2017

Caratteri glagolitici disegnati in pietra e fatti intagliare in rame da Luca Orfei, Roma, 1589 (Glagolithic characters designed in stone and printed in copperplate by Luca Orfei, Rome, 1589)

So I want to look at the Glagolithic alphabet, the oldest Slavic alphabet system. What got me interested was a dust up between Kyiv and Moscow over the Anna Yaroslavna, or Anne of Kiev, over the origins of the Évangélaire de Reims a few days ago.

The the Évangélaire de Reims, also known as the Reims Gospel or Slavonic Gospel, is over 1,000 years old. From a Ukrainian perspective, it is an important symbol of nationhood and independence. Anne of Kiev was married to Henri I — the book (which subsequent kings would use in coronation) is believed by many to have been brought by her into France. The Reims library has a section on its web site in disputing this which they've gone to the trouble of translating into Russian.

Évangélaire de Reims detail in Cyrillic detail—beautiful strokes in this

This interview with Talia Zajac about Anna Yaroslavna is pretty fascinating: she occupies a space in between the Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches. "My article showed that it is not helpful to think of her as an “alien” or “exotic” queen; adjectives which are tinged with Orientalist overtones. Rather, Anna’s queenship exemplifies a fluidity of religious-social identity: she both adapted to the roles and expectations of western queenship conferred to her upon her crowning and anointing, and, at the same time, as seen in her Cyrillic signature or the Greek name given to her eldest son, continued to have some degree of contact and connection to the Orthodox land of her birth. Her reign can give us insight into the ways in which “foreign” medieval queens successfully negotiated these fluid identities." Anna introduced the Greek name Philip, through the name of her son, to the royal families of Europe, signifying a connection between Western Europe and Eastern Europe. I had never really made the connection between Ukrainian and Greek alphabet systems, even though, now that I see it laid out it is obvious that they have a strong cultural/religious connection and this would show up in written language.

Recently in Kiev a statue of her was put up depicting her as a princess holding a book, and dubbed the 'granny of 30 kings' (her own accomplishments make this my least favourite definition of her). I have the sense that symbolically to Ukrainians she represents culture, independence from Russia, learning, and stewardship. So in that respect, her actual connection to the gospel isn't really that important. She's connected to it in the popular imagination. This is my perspective from a communications point of view, I would expect a historian to feel very differently.

I am no expert on medieval Slavic history — I have Ukrainian heritage but know very little history and no language — but I'm interested in the significance of the typography and of the publication. (As an aside, I just want to point out that Anne of Kiev's braids look amazing: a French queen with Ukrainian and Swedish heritage is obviously going to have some gold standard braids.)

Statues of Anne of Kiev holding a book and the Church, and her Cyrillic signature "Ана Ръина "Anna regina" which may have been written a proxy. The presence of her signature, or other references to her in government documents is unique in French history and points to her active and respected participation in governing.

The original gospel was supposed to have come with jewels and possibly a fragment of the cross or a relic (The French and English wikipedia pages on this have slightly different information about this...yes I wikipedia'd). It was lost during the French Revolution, later found again without the jewels or relics. The two sections of the book were created at different times. Later a facsimile (or two) were created.

The Reims library has archived and digitized it (Reims, Bibliothèque municipale Carnegie, MS 255).

The book itself is in two sections: Cyrillic and Glagolithic:

The Glagolithic section of the Reims Gospel was written in Moravia in the late 1300s.

The later Cyrillic section — I believe it's Bulgarian in origin.

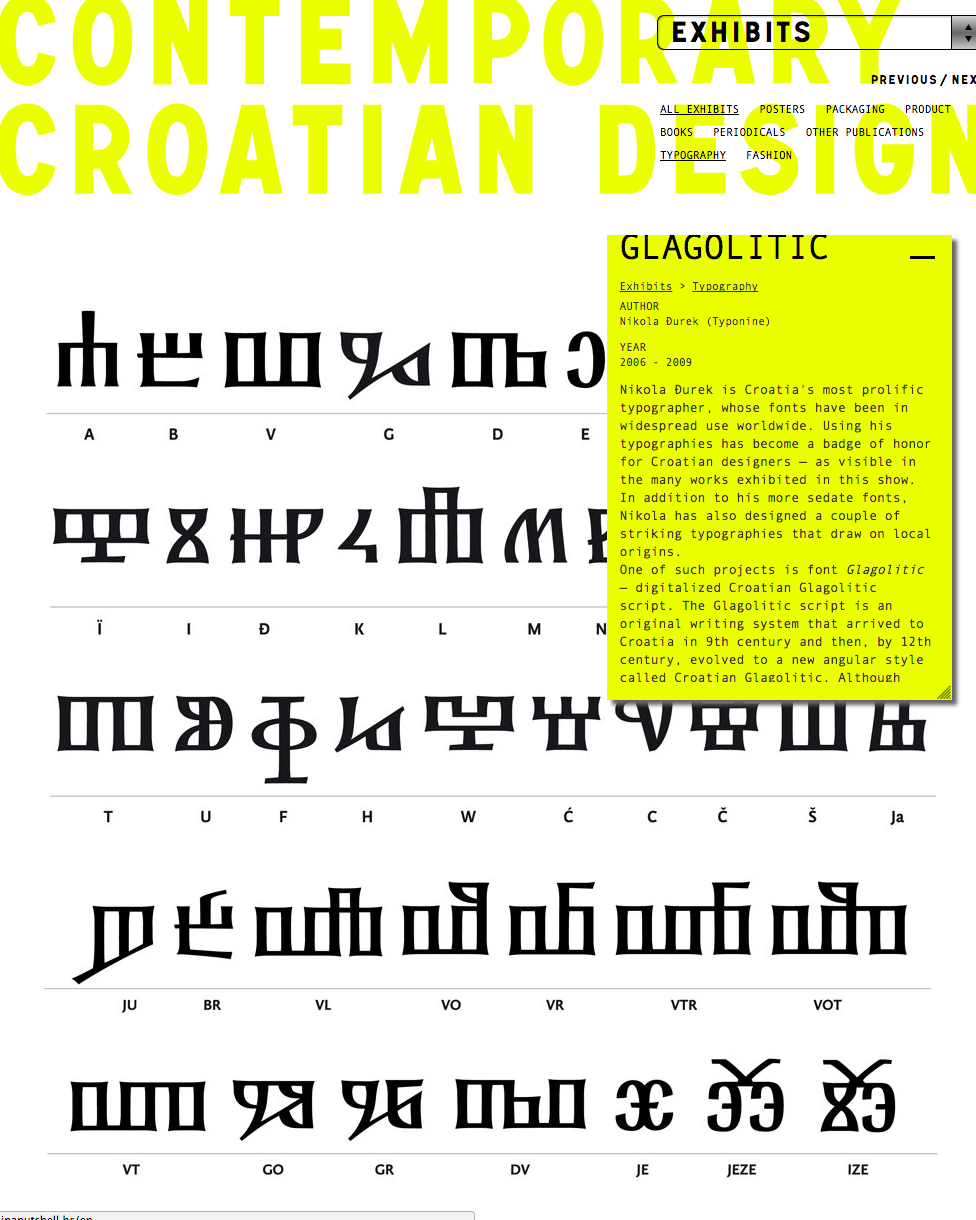

The Glagolithic alphabet is the oldest Slavic alphabet, used until the 20th century in Croatia, where it was eventually replaced with the Latin alphabet. "The question of the origins of the Glagolitic Script seems to be still a difficult open problem. In the earliest period it also existed in Ukraine, Bulgaria and Macedonia, but only until the 12th century, when the Cyrillic Script (which is essentially a Greek Script) became predominant."

Part of a title page and the section on Croatian alphabet in a multi-lingual text called Daniels Copy-Book

The earlier versions of the alphabet are quite triangular in shape, very different then the rounded Carolingian alphabet developed in western Europe that would serve as a basis for the Latin lowercase alphabet. Later it becomes more rounded. A lot of the earlier typographic samples are in stone. I wonder if there's any possibility that writing in pen helped create a more rounded look over time that would make it easier to write more quickly? (If you happen to be a student coming across this, please don't quote me on this last bit, I'm just thinking out loud). There was a variation called quick-script which contained about 250 ligatures, described as "building-like" linking up to 5 letters at a time. "The Croatian Glagolitic Script has very probably more ligatures than any other script in history."

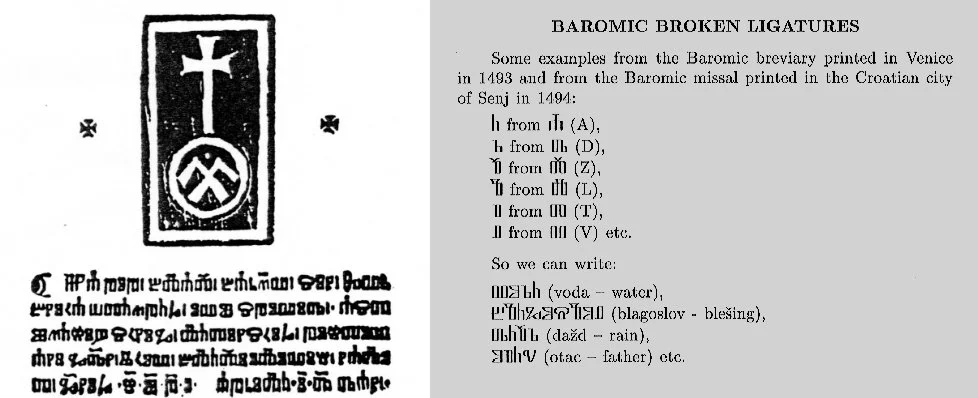

This is also pretty interesting: "The broken ligatures created by Blaž Baromić (14/15th centuries) represent a unique phenomenon in the history of European printing. The idea was to add one half of a letter to another. This possibility arose from the architecture of Glagolitic letters. Broken ligatures appear in two incunabula: the Baromic breviary printed in Venice in 1493, and the Baromic missal printed in the Croatian city of Senj in 1494. When looking at their pages, one has the impression as if they are handwritten." Blaž Baromić was a printer. I think the idea of half ligatures or multiple letter-ligatures is an interesting solution to shorthand text.

Left: Blaž Baromić's Senj press insignia via ellerman.org and an example of Baromic broken ligatures from croationhistory.net

I wish I had more time to look into this system. It wouldn't really fit into my typographic lectures, it's too specific. However, I'll leave it here so I can come back to it at a later time. If you know anything about the Reims Gospel or the Glagolithic alphabet, let me know. It's a very beautiful system.